(Bloomberg) -- The battle for the future of Australia’s climate policy is no longer about whether to cut carbon emissions -- it’s about how fast to act.

Article content

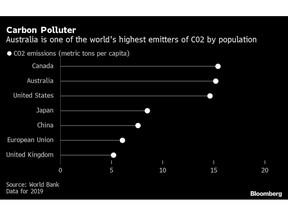

(Bloomberg) — The battle for the future of Australia’s climate policy is no longer about whether to cut carbon emissions — it’s about how fast to act.

Advertisement 2

Article content

On one side, pro-climate lawmakers who control the balance of power in parliament are pushing for sharper cuts and radical policies like banning new coal and gas mines. In the other camp, big business who are committed to some change but fear rapid movement will imperil an economy reliant on fossil fuel exports.

Article content

Trying to balance these competing interests is Australia’s new Prime Minister Anthony Albanese who won power with a pledge to end the country’s “climate wars” — a term for the decades of inaction and division which paralyzed energy policy and earned Australia an international reputation as a climate laggard.

This week, parliament passed Albanese’s signature climate legislation mandating emissions cuts of 43% off 2005 levels by 2030. The target brings Australia in line with nations including Canada, South Korea and Japan but fails to match key allies including the US and UK who are aiming for cuts above 50%. The legislation is also largely symbolic, leaving the detail on how the cuts will actually be achieved to future debate.

Advertisement 3

Article content

“That was round one,” said Greens leader Adam Bandt, who had argued for tougher standards. “The new government is going to need to be pushed further and faster.”

Parliamentary mathematics means the government must negotiate with pro-climate action politicians if it wants to pass any of its agenda easily. While Albanese holds a majority in the lower house of Parliament, in the Senate he needs the 12 votes held by the Australian Greens and one from an independent senator.

“We are going to fight tooth and nail,” Bandt said.

The Greens want cuts of 70% by 2030, while independent pro-climate lawmakers, like balance of power Senator David Pocock, are calling for reductions closer to 60%. That’s a tall ask for a country where coal and gas count for almost a quarter of total exports in the 2019/2020 financial year, according to the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Advertisement 4

Article content

The major upcoming skirmish will be over the government’s safeguard mechanism, a carbon pricing policy under which high-polluting companies will be forced to reduce emissions or pay costs. Pro-climate politicians including Bandt want this to be strong enough to make any new fossil fuel ventures unprofitable.

That’s a deal breaker for the business community, who have historically argued gas is needed as part of the transition to renewables.

Abandoning coal or gas too rapidly would be “extremely disruptive” to business, Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry CEO Andrew McKellar said, labeling the targets proposed by the Greens and Pocock “completely unrealistic.”

“There’s no conceivable pathway there without very, very significant transition costs being imposed upon the economy,” McKellar said. “I think that would once again run the risk of fracturing the consensus.”

Advertisement 5

Article content

Threading the Needle

It took less than three months in power before Albanese’s interests diverged from the pro-climate action lobby. In August, the government approved the opening of almost 50,000 square kilometers (19,300 square miles) off Australia’s coastline for petroleum exploration.

Climate activists were livid. Albanese was unrepentant. “People still put petrol in their cars,” he said.

He’s rejected the idea of moving faster on overall cuts, arguing the government has a duty to stick to the proposals it took to the 2022 election.

Hanging over the debate is the knowledge this week’s legislation is the first major new climate law in over a decade. In 2011 the then-Labor government passed measures to put a price on carbon emissions, a move which was seen by some as a broken election promise and led to years of fractious debate. The carbon price was repealed just two years later by the center-right Liberal National Coalition, which had campaigned against the measure and won an election in 2013.

Advertisement 6

Article content

Instead of moving quicker, the government wants to make progress on smaller targets.

Energy Minister Chris Bowen has floated the possibility of introducing fuel efficiency standards for imported vehicles. Funding for Labor proposals, including rewiring Australia’s electricity grid, is likely to be included in the government’s first budget in October.

Labor has also pledged to rapidly accelerate Australia’s usage of electric vehicles, including by investing in a national network of vehicle charging stations.

The question for the climate-politicians will be how hard they push the government and whether they are prepared to jeopardize Albanese’s leadership, considering the alternative could be the return to power of the Coalition.

Advertisement 7

Article content

Under Scott Morrison, Australia was the only nation to score zero in a review of climate policies among 60 countries and the European Union conducted by the Climate Change Performance Index.

Crucial swing vote Pocock said he is prepared to compromise — as long as progress is made. “I’m there to be constructive, to actually ensure we can ramp up ambition on climate,” Pocock said, adding he wouldn’t let “perfect get in the way of action.”

For many businesses, the stability of a mandated emissions target is the change they’ve been craving for years.

And Anna Bligh, head of the Australian Banking Association, said the reality now is the 43% target is a floor not a ceiling.

“We need to stop arguing about these things and get on and start changing the basis of our economy,” she said.

Advertisement

Australia's Next Climate Struggle Is How Fast to Cut Emissions - Financial Post

Read More

No comments:

Post a Comment