Time did not seem to be on Chris Xu’s side when he threw himself into the cut-throat world of Chinese entrepreneurship. He quit his job in marketing and set up an online fashion retailer just as the 2008 global financial crisis struck.

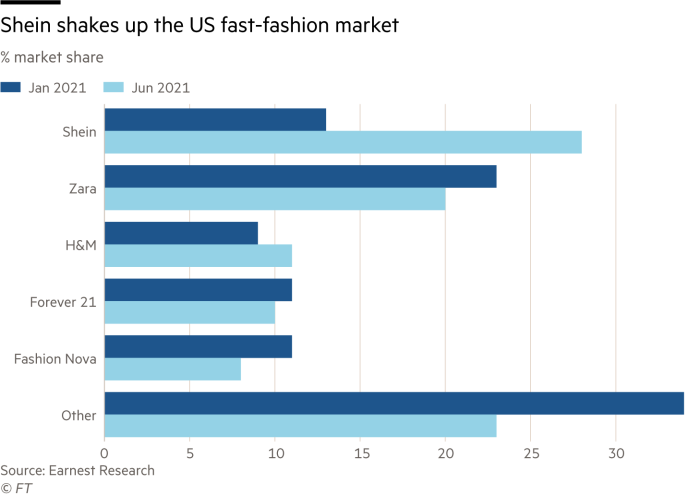

Yet after little more than a dozen years, Shein, the company he founded, has seized over a quarter of the US fast-fashion market and its rapid growth threatens to disrupt established global players such as Spain’s Inditex and Sweden’s H&M.

The business is built around the fast-fashion model pioneered by others, including Inditex’s Zara. But through use of automation, artificial intelligence and a well-drilled supply chain, Shein has found a way to do it both cheaper and faster.

The company’s detractors say its business model relies on tax loopholes, a flexible attitude to intellectual property and scant regard for corporate and social responsibility. “I think it should be closed down,” grumbles the chief executive of one big fashion retailer.

But its young consumers appear to care little and Shein’s rock-bottom pricing plus its growing dominance in mobile apps and social media favoured by that cohort has started to cause concern in western boardrooms.

In the first few months of 2021, its app downloads were second only to Amazon and its engagement levels on TikTok were notably higher than those of rivals.

Despite such a rapid rise, there is little public information about the company or its enigmatic founder, beyond that it started life selling Chinese-made goods from sunglasses to wedding dresses for export to individual customers in the US, and that it changed its name from SheInside to Shein in 2015.

In the process, Shein has become one of the few Chinese consumer brands to break through in the US and European markets. The company’s competitiveness also calls into question the notion that the era of super-cheap manufacturing in China is over.

“We didn’t come out of nowhere,” says George Chiao, head of the company’s operations in the US, where Shein this year surpassed H&M and Zara to become the largest fast-fashion retailer by sales, according to retail data analytics company Earnest. “We spent the past 10 years building the foundations of the company.”

He adds: “It has been difficult for Chinese brands to go to the west and make a name for themselves”.

‘Test and repeat’

Inditex, the world’s biggest apparel retailer, pioneered the idea of quickly adapting catwalk styles into clothes that could be bought by ordinary consumers in stores. The likes of Boohoo in the UK and Fashion Nova in the US used a “test and repeat” model — producing small amounts of a range of styles — to accelerate that process to just a couple of weeks.

But Shein has taken that down further — to as little as a week — and at much greater scale. Each day, it adds 6,000 new items online, far more than any comparable retailer manages. It responds in real time to trends picked up not by fashionistas and designers but by analytics software, which trawls through shopping and social media websites.

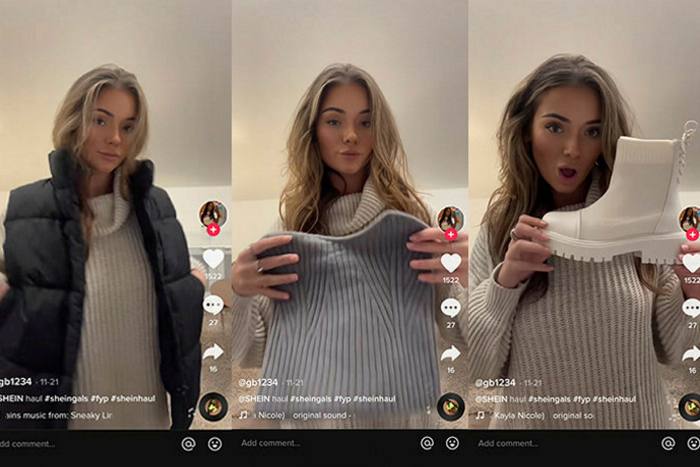

While established fashion retailers rely heavily on Instagram, especially for social media promotion, Shein has piggybacked on the growth of TikTok, the Chinese short-video app that has also become wildly popular around the word.

For Gen-Z consumers, the company has become synonymous with the TikTok phenomenon of influencers posting short clips of “Shein hauls”, parading an array of outfits to their online fans.

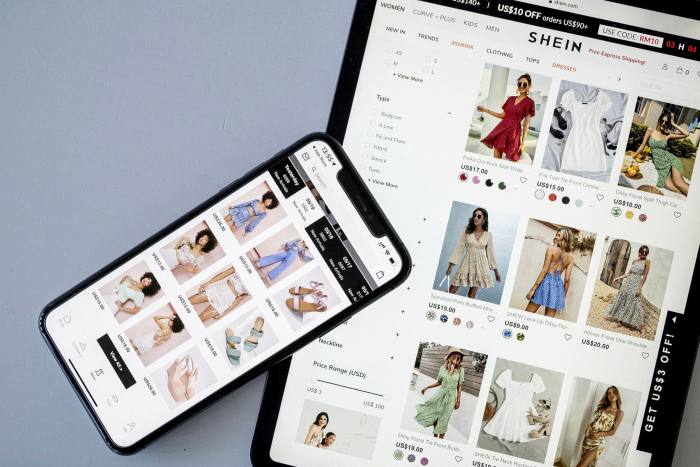

Shein also makes a much greater proportion of its sales via mobile apps rather than conventional websites and has borrowed ideas from the world of gaming — such as countdown clocks and even games with discounts as prizes — to boost engagement and spend in that channel.

Before shoppers check out, Shein’s app entices them to continue adding to the basket with the lure of gifts and express delivery if they hit a certain spending threshold. Although such practices are common among fast-fashion retailers, Rouge, a website and branding agency, found that Shein included more prompts to users to spend more money or disclose personal data than any other.

Dimitrios Tsivrikos, a consumer psychologist at University College London, says that Shein has turned shopping into a form of online entertainment. “Social media has been a very effective promotional outlet for Shein, especially with the rise of TikTok.

“Young people can only wear the same clothes once or twice before eventually throwing them away for fear of being labelled ‘cheugy’,” he adds, referring to a pejorative teenagers use to poke fun at the unfashionable and outdated.

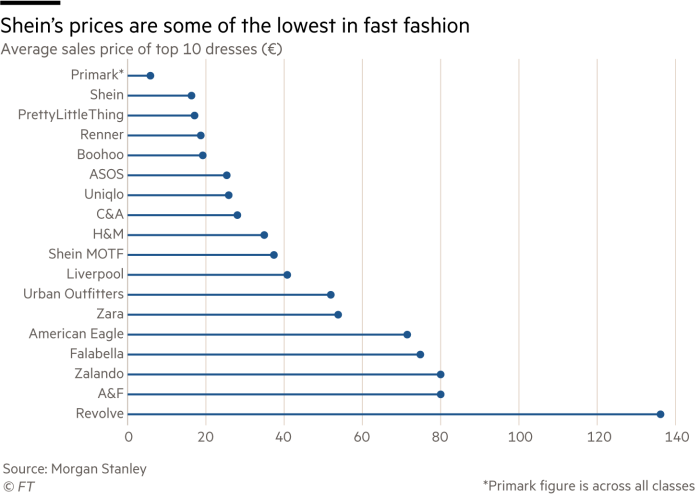

Shein is also very cheap. The average unit price for its more than 600,000 products is just $7.90. Analysts at Morgan Stanley found that only Primark in Europe — which operates a traditional model of long lead-time manufacturing in south Asia — and Forever 21 in the US could consistently match it on prices of staples such as jeans, dresses and T-shirts.

Industry competitors question how Shein is able to sell its wares so cheaply, given that labour costs in China have been rising for years, and that more recently the Covid-19 pandemic has inflated prices for everything from fabrics to air freight.

“We have tried to model it and we just couldn’t make it add up,” says one senior UK fashion executive. “A lot of the clothes are very simple but the quality isn’t bad for the price points.”

He and many others point to the tax advantages that Shein enjoys. Most fashion retailers build a presence in their home market before expanding overseas, but Shein has never sold clothes in China itself. Instead it exports, largely using air freight, from its manufacturing base in Guangdong to key markets such as the US and Europe.

Those transactions are free of export taxes in China and only a tiny minority of its shipments overseas incur import duties; the threshold at which consignments into the US qualify for assessment is $800, in the UK the equivalent is £135 and in Europe it is €150.

Because Shein ships individual parcels from its base in southern China, almost all its packages fall below this threshold and are not subject to import duties in the US or Europe. This allows them to undercut rivals whose merchandise is subject to sales taxes.

In addition, for much of its existence Shein benefited from discounted shipping rates owing to China’s classification as a “developing country” within the Universal Postal Union, the UN agency that co-ordinates postal policies, though changes made in 2020 have reduced the impact of these.

Shein also insists that it does not undercut rivals by effectively subsidising operating expenses such as air freight costs. Instead, it points to its supply chain system within China. “We keep our margins very low, reinvesting the money to improve and iterate our business,” says Chiao.

Its manufacturing capacity is concentrated around Panyu, the industrial district of the southeastern province of Guangdong. “Chinese people have been very good at manufacturing,” says Chiao. “Why? Because they lock themselves up in a factory and make products westerners ask them to make.”

He says Shein uses both suppliers who design their own products and pitch it to Shein’s buyers and “contract manufacturers who exclusively work for us”. Both are expected to do small-batch production runs.

“It took 10 years to build these supply chains because most suppliers don’t want to sell you only 100 pieces,” he adds. Payment terms were one way of convincing them. “We started with 30 days, unheard of at the time. We were able to get buy-in for Shein’s way of sourcing.” Standard payment terms for garment companies to pay factories can be 90 days.

It also insisted that suppliers use its cloud-based supply-chain management software, unusual in what is often still a low-tech industry that runs on personal relationships. As a result of this integration, product lines that sell well are automatically reordered in larger volumes, according to one consultant who has worked with the company.

Shein is able to pay suppliers quickly because its just-in-time model means very little cash is tied up in inventory. Its reliance on third-party logistics operators and lack of physical stores has also meant its growth has not required much capital.

Figures from PitchBook suggest that its growth to an estimated $10bn of annual sales, according to Bloomberg reports citing unidentified sources, has been supported by total equity investment of little more than $500m. This came from Tiger Global Management, Sequoia and Jafco Asia among others. All three declined to discuss their involvement.

Repeat customers

It is hard to know exactly how much disquiet Shein’s growth is causing in an industry that is well used to fickle consumer tastes and vigorous competition. “I’ve seen a lot of things in fashion that have come out of nowhere,” says one former senior executive in the sector. “Some crash and burn, some go on to have a profound impact. It’s not yet clear to me which bucket this one falls into.”

Pablo Isla, who as chief executive and executive chair masterminded Inditex’s massive global expansion from 2005 onwards, confined himself in a Financial Times interview earlier this year to noting that “there is not just one business model that can prove successful”.

But Michael Maloof at Earnest Research in New York, who has tracked Shein’s rapid growth in the US in recent years, says “there is genuine concern” among executives he has met from established fashion retailers. “The US is a huge market for many of them.”

He pointed out that not only was Shein winning new customers, but that based on the US credit and debit card transaction data that Earnest analyses, its repeat purchase frequency was also high. He says its customers seem to regard its low prices as an acceptable trade-off for any variable quality and longer delivery times than many of its rivals.

Unsurprisingly, given its growth and unusual modus operandi, controversy has followed Shein. It has been accused of copying designs from multinationals such as Dr Martens and Levi’s to individual designers such as UK-based entrepreneurs Deborah Breen and Sarah Vaughan.

Shein says it responds promptly and fairly to any accusations of intellectual property theft. And Chiao argues that the company is now supporting independent fashion designers such as Reia Toombs, one of a group of designers now producing special lines for Shein. She says the company supports her dreams of being a successful fashion designer: “The cost of running my brand was too high. But now the company pays for my manufacturing and marketing costs.”

Working conditions in its supply base have also come under scrutiny. The company says it treats staff at contract manufacturers well, paying garment makers an average salary that is 45 per cent more than the national average. But an investigation by Sixth Tone, a Chinese online magazine, found many of Shein’s manufacturers cut costs by outsourcing to small workshops that pay their workers less and frequently flout labour laws — a complaint that has also been levelled at the UK’s Boohoo. Chiao says Shein auditors check up on its outsourced manufacturers and the company brings disciplinary action if it finds a problem.

Environmental groups have condemned it for contributing to soaring levels of clothing pollution. The fashion industry accounts for about 5 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions and, by some estimates, fewer than 1 per cent of garments are recycled.

Chiao said Shein is trying to “actively mitigate” its environmental impact through its small-batch sourcing model which prevents large amounts of unsold stock going to waste, but was unapologetic about accusations of stoking demand for disposable clothing. “This is what consumers want,” he says.

Shein is also gradually moving away from both its focus on the ultra-cheap end of the market and its historical aversion to publicity. It has launched a more upmarket label, known as MOFT, which uses better quality fabrics but is still priced below mass-market equivalents.

This year it bid for Topshop, the UK fashion brand that was the jewel in Sir Philip Green’s collapsed Arcadia empire, though it lost out to Asos.

“In the past, people have [said] we are being intentionally mysterious for some nefarious reason, but the truth is we’ve just been keeping our heads down and working,” says Chiao. “But at this stage, we are selling clothes to the west and people want to talk about us. We’re ready to be more engaging now.”

Some are already taking note. In October, analysts at investment bank Morgan Stanley cut its medium-term forecasts and share price targets by up to 34 per cent on 15 major fashion groups, listed across Europe, the US and Latin America, that they considered particularly exposed to the rapid growth of Shein.

“We think that the recent disappointing performance of several European online retailers could actually be partially linked to Shein’s emerging success,” they said.

Most of all, it was concerned at what the emergence of such a formidable operator in a comparatively short space of time implied about barriers to entry in the sector. Shein’s rise suggests “that other similar or even more disruptive players could well emerge over the next 10 years, further increasing the competitive pressure in this market”.

Shein: the Chinese company storming the world of fast fashion - Financial Times

Read More

No comments:

Post a Comment